Did The NWS Blow It?

Floods are unpredictable and hard to forecast. We explore the mechanics behind the devastating floods in the Hill Country and the criticism levied at the National Weather Service.

Predicting flash flooding, and devastating floods in general, is a lot like forecasting tornadoes. We have the tools and the knowledge to predict the ingredients and identify a pattern that can produce a once in a lifetime flooding event, but knowing where the bullseye sets up is much like trying to predict exactly where a supercell will pop up and slab your house on a high risk day. It’s just not easy until the storm is on top of you.

As I’m drafting this, at least 70 have died in the floods in Central Texas. Search and rescue teams are underway, looking for a summer camp in Kerr County where 11 campers and a camp counselor are still unaccounted for. It’s an unimaginable tragedy and my heart goes out to the families of those who have been killed in the floods, as well as those who lost their homes and belongings in the flooding.

The Ingredients

Floods, severe thunderstorms, and tornado outbreaks share three of the same ingredients with each other, which is convenient for remembering them. Those ingredients are lift, instability, and moisture. Lift kicks everything off; you usually need bubbles of air to be forced upward to create storms and clouds. What happens when a bubble is lifted depends on instability and moisture. Instability is usually measured via CAPE (convective available potential energy) and is a measure of how much energy a rising bubble can tap into. It’s useful for determining how powerful updrafts can be in supercells in addition to forecasting if deep convection is possible. Finally, we have moisture… which is just how much water you have in the air to produce clouds and rain in the first place!

Unlike thunderstorms, you don’t need a large amount of CAPE for showers and heavy rain. High CAPE is useful for the strong, violent updrafts you see in supercell thunderstorms, though even with 1000 J/kg CAPE you can get solid development into stratus clouds and sustained convection. We saw between 1000 and 2000 J/kg of CAPE here.

The core differentiator is the wind. Supercells and tornado outbreaks rely on winds that move fast, and change direction with height (known as wind shear). Flooding is almost the complete opposite, you want a broad, slow-moving body of wind that is unable to steer storms away from a location. This kind of wind means that storms and convection bubble up on one area and stay planted for hours on end.

The Barry in the Room

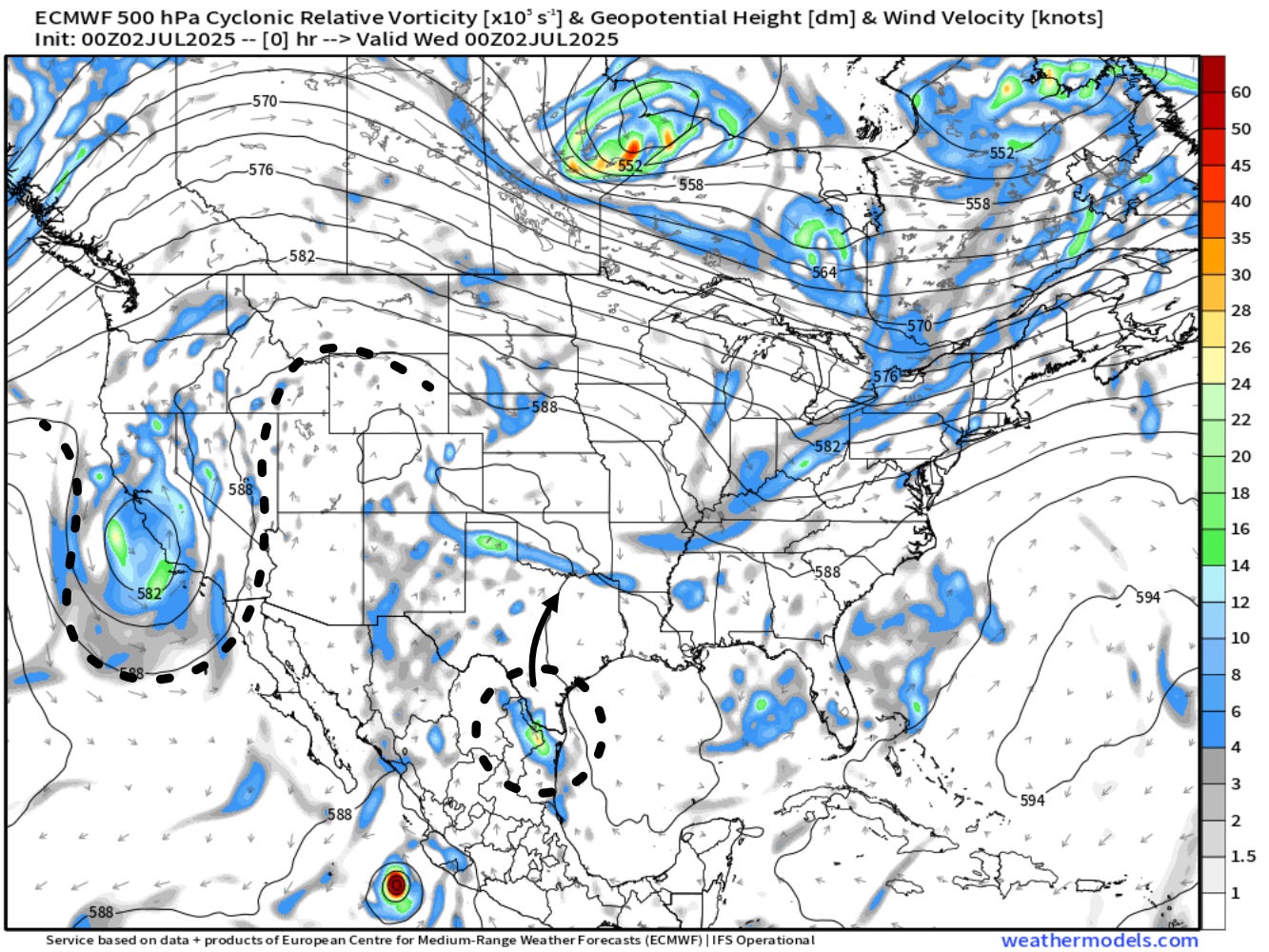

I think it's time to introduce the main player for this event… remember Tropical Storm Barry? It was a bit of a ragged mess and made landfall near Tampico, producing some flooding rains as the surface circulation was shredded apart by terrain. But notice how I said surface circulation. Tropical cyclones, can sustain their upper level rotation for far longer than their surface circulation may last.

This circulation powers a metric known as vorticity, literally a measurement of how fast the air is spinning at a given point. Vorticity is a powerful indicator for identifying upper air divergence in the atmosphere. What happens is that air will rise up, run into the tropopause (the boundary between the lowest level of the atmosphere, the troposphere, and the stratosphere), and be forced to spread out. We can look at that to determine where air could be getting forced up, lifting warm parcels of air that tap into moisture, which later condenses into clouds and precipitation.

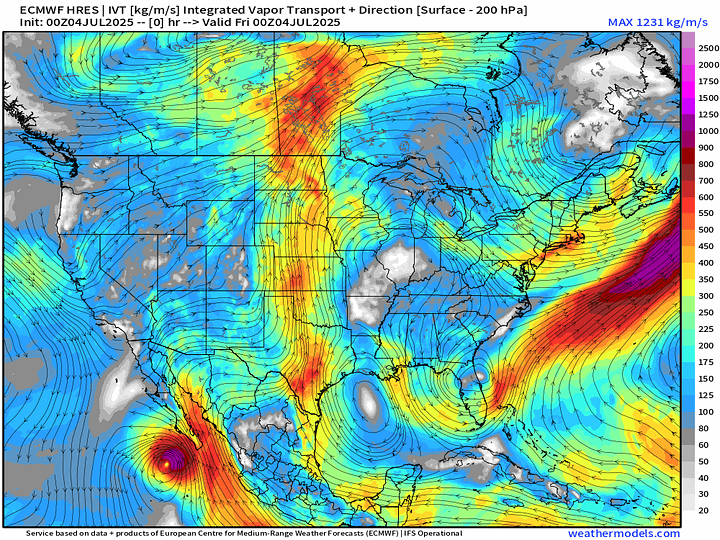

This is just two factors, though. You need a few more factors interacting with each other to create a catastrophic flooding event. Here is where we need to introduce our third factor – moisture. Even very weak tropical cyclones are fueled by a mass of water vapor that is indescribably moist and deep. Downstream of these cyclones, hiding away in the upper atmosphere, is a torrent of tropical moisture, ready to be tapped into.

Our second foe is seen on the left side of the map, a trough situated over central California. It’s decaying, and will eventually interact with the remnant bubble of vorticity from Barry. This is problematic for two reasons. The decaying trough means upper level winds are slowing, keeping the same storms bubbling over an area for longer. Secondly, the fact there is a trough in the first place is yet another source of vorticity that can lead to lift and convective storms.

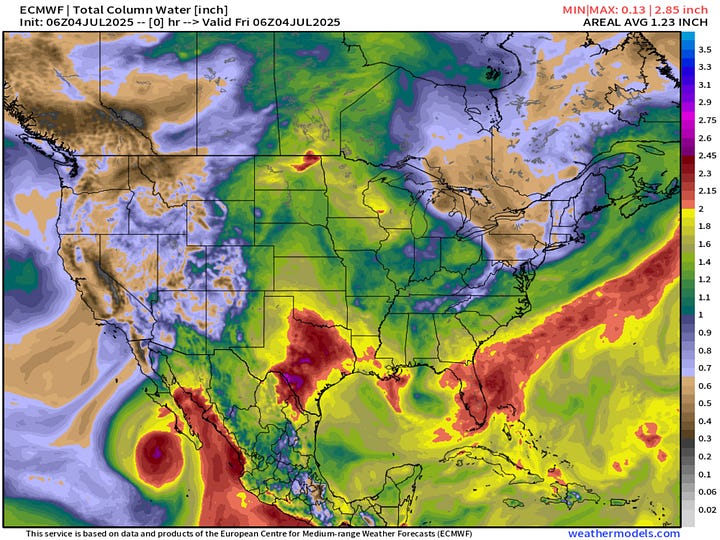

All of this interacted with deep moisture content throughout the atmosphere. A weather balloon launched from Corpus Christi on the evening of July 3rd indicated about two inches of water in the atmosphere (precipitable water is the more formal term for this, and it refers to how much water could fall out of the atmosphere if condensed immediately). According to SPC climatology for this site, that is at the 90th percentile for moisture content in the air.

Unfortunately, precipitable water is just one piece of the puzzle when deciphering intense rainfall events. The air is a fluid, and it can be moved around from place to place. Model runs often compute a metric known as 'integrated vapor transport,' which measures how much water vapor is moving through the atmosphere, and from what direction. In this case, we saw a river of water being funneled into the Hill Country, replenishing the moisture tapped from the existing atmosphere.

Devastation

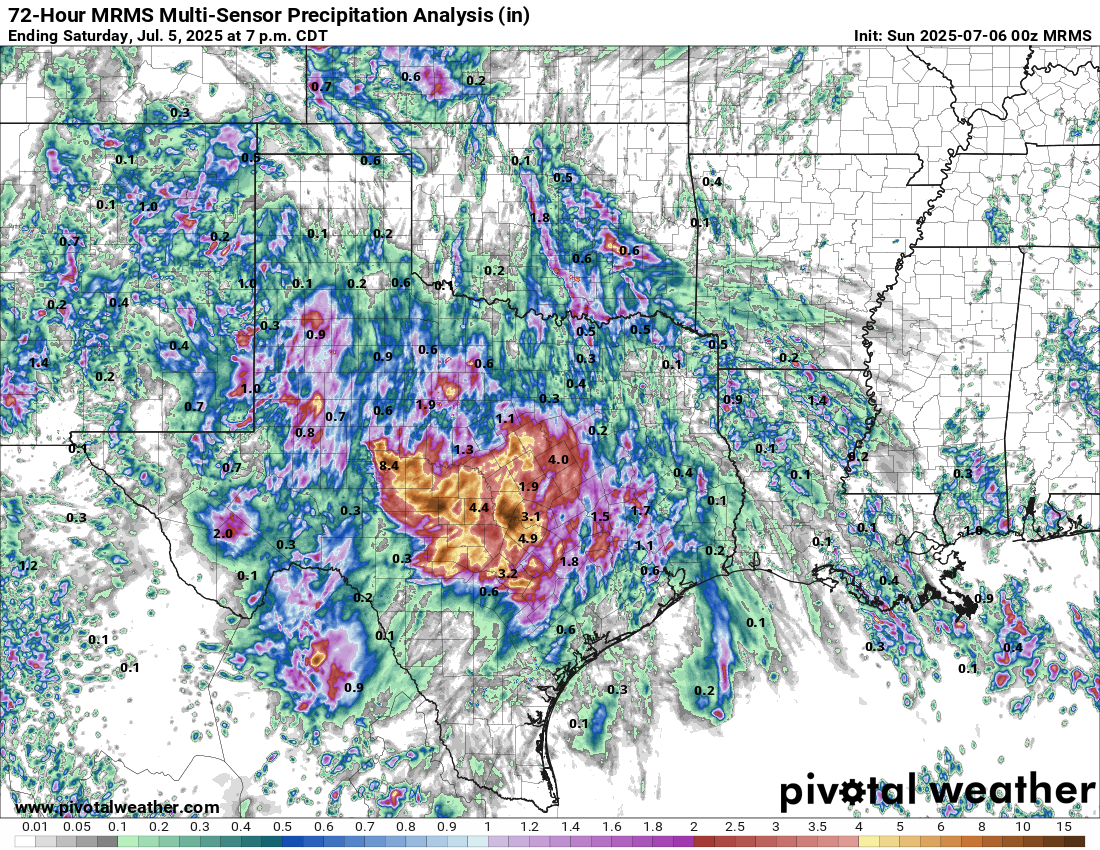

The results have been devastating. As mentioned in the intro, dozens have been killed, many have had to be rescued from their homes, and there’s currently no telling how many are unaccounted for. The human toll is horrific.

I do want to be clear that this isn’t unusual; the Hill Country frequently experiences flooding events from this combination of atmospheric factors and topography that aids with forcing air up. But a tragedy of this scale is rare, and it’s always sad to see.

In many spots, at least 6 inches have fallen in the last 48 hours. Several have reported over 10 inches of rainfall from this event as well. We’ve seen rivers overflowing their banks, some rising 26 feet in 45 minutes. Flood warnings and flash flood emergencies began to be issued shortly after midnight on the 4th, and have continued through Saturday. Only in south-central Texas has the rainfall calmed down, with the system lifting northward and impacting areas just south of the metroplex.

The Forecast

Forecasting floods is hard. There is a bit of a disconnect between how they’re treated as opposed to tornado threats. With a tornado watch, there’s an implicit understanding that all areas have a chance even if nothing can be predicted until it pops up. Flooding though? The public is much less lenient regarding busted forecasts. People want to know specifically when and where, and it’s really hard to do.

It’s possible to give guidance. The Weather Prediction Center issues Excessive Rainfall Outlooks and National Weather Service offices issue watches and point forecasts within their warning area. However, predicting where the mesoscale features will work with each other to fire up a storm that dumps 20 inches of rain in a single location is much like predicting exactly which warm bubble will lift up and turn into a supercell thunderstorm.

I’ve seen a lot of the blame game go around suggesting that the NWS and NOAA fumbled the ball here, and stating that they didn’t warn people in time. I think this is incorrect.

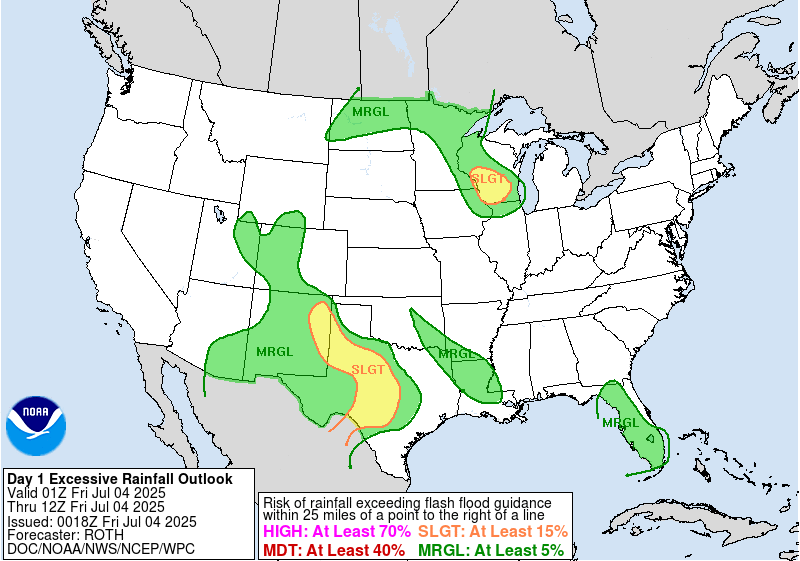

The Weather Prediction Center was signaling late on July 3rd that there was at least a 15% risk for flash flood conditions throughout much of the area. In their discussion, they noted how hard this was to forecast and mentioned a few signals of uptrending in recent model runs:

Given precipitable water values in the 2.25"+ range, this could equate

into hourly amounts to 3" where storms can train, backbuild, or

merge. Across South-Central TX, the 18z HREF signal for 5"+ (over a

small area) and 8"+ (in one spot) through 12z was greater than

50%, which was troubling. Believe this environment is at the high

end of a Slight Risk -- possible localized Moderate Risk impacts

cannot be ruled out should convection persist for several hours.Models

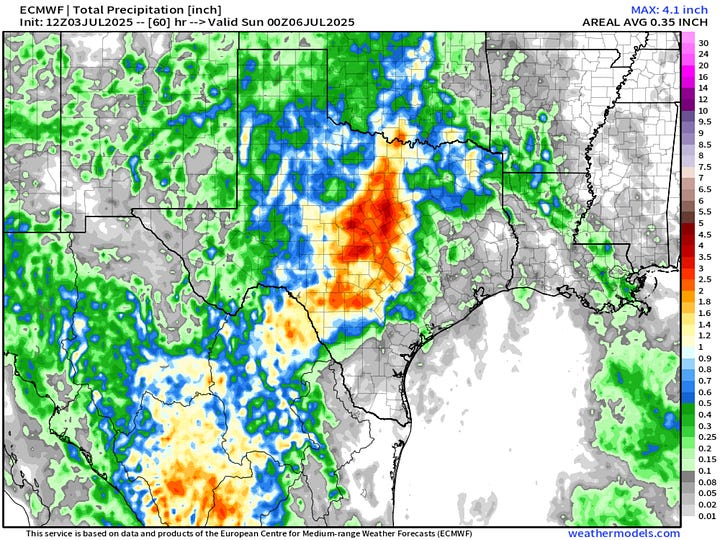

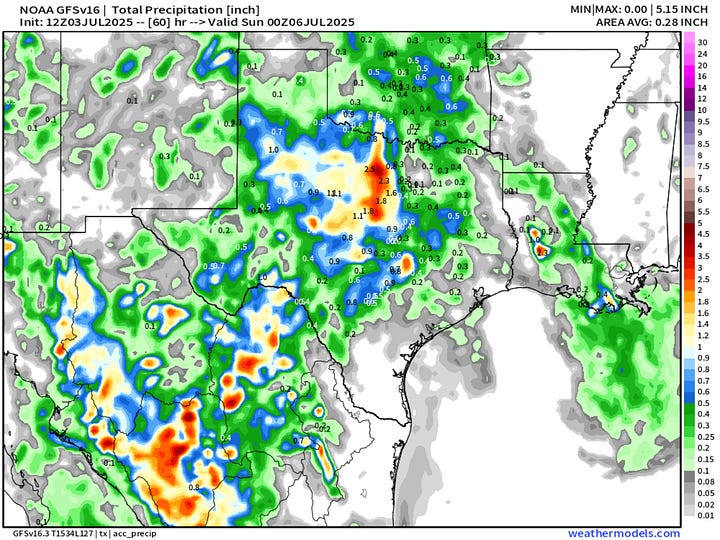

Model runs ahead of the event were all over the place, but even as early as the runs late on July 2nd, there was increasing consensus that a heavy rain event would occur. Global models are harder for identifying specific pockets of rain as their resolutions are on a global scale (the Euro has a horizontal resolution of 9km, GFS 21km). Flooding and convective precipitation are mesoscale features, working on a scale much smaller than 9km. Even with that in mind, we saw a consensus of 2-4 inches, and a first signal that this could be a rainmaker.

The WPC

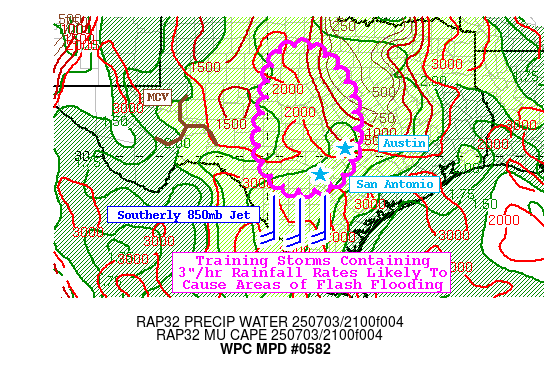

The WPC issues statements known as Mesoscale Precipitation Discussions. These are issued on the spot for features they identify as likely to cause significant flooding for an area. These are forecasting tools, mainly meant for fellow meteorologists, such as those in the private sector or on television, to use to communicate risk to their clients or viewers. They are also used by local emergency managers who can be made aware of threats and prepare accordingly. Below was the first MPD issued for this event, #0582. It was issued at 6:10pm CDT on July 3rd, and rang alarm bells that a flooding threat was likely to occur within the next several hours overnight.

The WPC took the time to identify all of the features interacting to create this flooding event, such as the instability in the atmosphere as well as how unusually soaked the atmosphere was throughout. They discussed that the atmosphere is "supportive of not just the potential for >3"/hr maximum rainfall rates, but for back-building and training thunderstorms over the Hill Country," warning of the imminent threat.

The NWS

The NWS is the agency ultimately responsible for disseminating warnings, and they did by all accounts. The office in New Braunfels issued their first flood watch at 1:18pm CDT on July 3rd. This was followed by San Angelo issuing their flood watch just 12 minutes later. Both of these warnings emphasized the risk of up to 1-3 inches of rainfall, with the risk of causing floods; New Braunfels noted localized risks of 5-7 inches. The New Braunfels office includes the county of Kerr, whose County Judge was the first in criticizing the lead time given to him and his emergency managers by the NWS.

Both offices continued to issue watches and alerts for the risk of flooding, and New Braunfels issued a flash flood warning at 1:14am CDT on July 4th, the first of seventy three issued during the event (San Angelo, for their part, issued 26 flash flood warnings in their warning area). They mentioned rainfall rates of up to 2-3 inches per hour and tagged it as a 'considerable' damage threat. This is notable, as since 2019, WEA (wireless emergency alert) notifications for flash flood warnings are only sent if a warning is tagged with considerable or catastrophic. In plain English: this will give people a shrill notification on their phones and wake them up if they are sleeping. The folks at the NWS tirelessly issued warnings and coordinated with local emergency managers to bring this information to the public.

But the cuts…

Okay, yes. This is an elephant in the room. The budget cuts, the reduction in staffing, the threats to NOAA. All of it.

But it wasn’t an impact here. At least for the New Braunfels office, they had extra staff on duty that night. We have to be realistic, those are serious threats to the Weather Service, but they performed admirably and were at the top of their game.

Sometimes things happen, and its not anyone’s fault.

All warnings were timely and people were given several hours of lead time. This was a very tricky event to forecast, though. It is difficult to know where a storm will set up shop and wash away a community, but we’re getting better at it. However, this progress is under threat as NOAA’s 2026 budget request eliminates all cooperative institutes, which have been testbeds for new models and forecasting techniques, which will, in the long-term, degrade forecasting capabilities.